This is the first in a series of posts about lessons from my experiences in World of Warcraft. I’ve been talking about this stuff for a long time—in forum comments, in IRC conversations, etc.—and this series is my attempt to make it all a bit more legible. I’ve added footnotes to explain some of the jargon, but if anything remains incomprehensible, let me know in the comments.

World of Warcraft, especially WoW raiding1, is very much a game of numbers and details.

At first, in the very early days of WoW, people didn’t necessarily appreciate this very well, nor did they have any good way to use that fact even if they did appreciate it. (And—this bit is a tangent, but an interesting one—a lot of superstitions arose about how game mechanics worked, which abilities had which effects, what caused bosses2 to do this or that, etc.—all the usual human responses to complex phenomena where discerning causation is hard.)

And, more importantly and on-topic, there was no really good way to sift the good players from the bad; nor to improve one’s own performance.

This hampered progression. (“Progression” is a WoW term of art for “getting a boss down, getting better at doing so, and advancing to the next challenge; rinse, repeat”. Hence “progression raiding” meant “working on defeating the currently-not-yet-beaten challenges”.)

Contents

The combat log

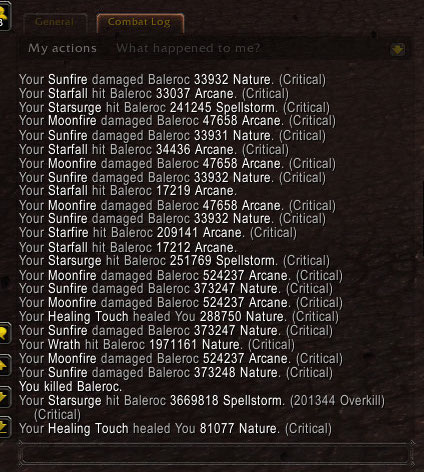

One crucial feature of WoW is the combat log. This is a little window that appears at the bottom of your screen; into it, the game outputs lines that report everything that happens to or around your character. All damage done or taken, all hits taken or avoided, abilities used, etc., etc.—everything. This information is output in a specific format; and it can be parsed by the add-on system3.

Naturally, then, people soon began writing add-ons that did parse it—parse it, and organize it, and present various statistical and aggregative transformations of that data in an easy-to-view form—which, importantly, could be viewed live, as one played.

Thus arose the category of add-ons known as “damage meters”.

The damage meters

Of course the “damage meters” showed other things as well—but viewing damage output was the most popular and exciting use. (What more exciting set of data is there, but one that shows how much you’re hurting the monsters, with your fireballs and the strikes of your sword?) The better class of damage-meter add-ons not only recorded this data, but also synchronized and verified it, by communicating between instances of themselves running on the clients of all the people in the raid.

Which meant that now you could have a centralized display of just what exactly everyone in the raid was doing, and how, and how well.

This was a great boon to raid leaders and raid guilds everywhere! You have a raid of 40 people, one of the DPSers4 is incompetent, can’t DPS to save his life, or he’s AFK5 half the time, or he's just messing around—who can tell?

With damage meters—everyone can tell.

Now, you could sift the bad from the good, the conscientious from the moochers and slackers, and so on. And more: someone’s not performing well but seems to be trying, but failing? Well, now you look at his ability breakdown6, you compare it to that of the top DPSers, you see what the difference is and you say—no, Bob, don't use ability X in this situation, use ability Y, it does more damage.

The problem

All of this is fantastic. But… it immediately and predictably began to be subverted by Goodhart’s law.

To wit: if you are looking at the DPS meters but “maximize DPS” is not perfectly correlated with “kill the boss” (that being, of course, your goal)… then you have a problem.

This may be obvious enough; but it is also instructive to consider the specific ways that those things can come uncoupled. So, let me try and enumerate them.

The Thing is valuable, but it’s not the only valuable thing

There are other things that must be done, that are less glamorous, and may detract from doing the Thing, but each of which is a sine qua non of success. (In WoW, this might manifest as: the boss must be damaged, but also, adds must be kited—never mind what this means, know only that while a DPSer is doing that, he can’t be DPSing!)

And yet more insidious elaborations on that possibility:

We can’t afford to specialize

What if, yes, this other thing must be done, but the maximally competent raid member must both do that thing and also the main thing? He won’t DPS as well as he could, but he also can't just not DPS, because then you fail and die; you can’t say “ok, just do the other thing and forget DPSing”. In other words, what if the secondary task isn’t just something you can put someone full-time on?

Outside of WoW, you might encounter this in, e.g., a software development context: suppose you’re measuring commits, but also documentation must be written—but you don’t have (nor can you afford to hire) a dedicated docs writer! (Similar examples abound.)

Then other possibilities:

Tunnel vision kills

The Thing is valuable, but tunnel-visioning on The Thing means that you will forget to focus on certain other things, the result being that you are horribly doomed somehow—this is an individual failing, but given rise to by the incentives of the singular metric (i.e., DPS maximization).

(The WoW example is: you have to DPS as hard as possible, but you also have to move out the way when the boss does his “everyone in a 10 foot radius dies to horrible fire” ability.)

And yet more insidious versions of this one:

Tunnel vision kills… other people

Yes, if this tunnel-vision dooms you, personally, in a predictable and unavoidable fashion, then it is easy enough to say “do this other thing or else you will predictably also suffer on the singular metric” (the dead throw no fireballs).

But the real problem comes in when neglecting such a secondary duty creates externalities; or when the destructive effect of the neglect can be pushed off on someone else.

(In WoW: “I won’t run out of the fire and the healers can just heal me and I won’t die and I’ll do more DPS than those who don’t run out"; in another context, perhaps “I will neglect to comment my code, or to test it, or to do other maintenance tasks; these may be done for me by others, and meanwhile I will maximize my singular metric [commits]”.)

It’s almost always the case that you have the comparative advantage in doing the secondary thing that avoids the doom; if others have to pick up your slack there, it’ll be way less efficient, overall.

Optimization has a price

The Thing is valuable, yes; and it may be that there are ways to in fact increase your level of the Thing, really do increase it, but at a non-obvious cost that is borne by others. Yes, you are improving your effectiveness, but the price is that others, doing other things, now have to work harder, or waste effort on the consequences, etc.

(Many examples of this in WoW, such as “start DPSing before you’re supposed to, and risk the boss getting away from the tank and killing the raid”. In a general context, this is “taking risks, the consequences of which are dire, and the mitigation of which is a cost borne by others, not you”.)

Then this one is particularly subtle and may be hard to spot:

Everyone wants the chance to show off their skill

The Thing is valuable, and doing it well brings judgment of competence, and therefore status. There are roles within the project’s task allocation that naturally give greater opportunities to maximize your performance of the Thing, and therefore people seek out those roles preferentially—even when an optimal allocation of roles, by relative skill or appropriateness to task, would lead them to be placed in roles that do not let them do the most of the Thing.

(In WoW: if the most skilled hunter is needed to kite the add, but there are no “who kited the add best” meters, only damage meters… well, then maybe that most skilled hunter, when called upon to kite the add, says “Bob over there can kite the add better”—and as a result, because Bob actually is worse at that, the raid fails. In other contexts… well, many examples, of course; glory-seeking in project participation, etc.)

Of course there is also:

A good excuse for incompetence

This is the converse of the first scenario: if the Thing is valuable but you are bad at it, you might deliberately seek out roles in which there is an excuse for not performing it well (because the role’s primary purpose is something else)—despite the fact that, actually, the ideal person in your role also does the Thing (even if not as much as in a Thing-centered role).

1 “Raid dungeons” were the most difficult challenges in the game—difficult enough to require up to 40 players to band together and cooperate, and cooperate effectively, in order to overcome them. “Raiding” refers to the work of defeating these challenges. Most of what I have to say involves raiding, because it was this part of WoW that—due to the requirement for effective group effort (and for other, related, reasons)—gave rise to the most interesting social patterns, the most illuminating group dynamics, etc. ⇑

2 “Boss monsters” or “bosses” are the powerful computer-controlled opponents which players must defeat in order to receive the in-game rewards which are required to improve their characters’ capabilities. The most powerful and difficult-to-defeat bosses were, of course, raid bosses (see previous footnote). ⇑

3 WoW allows players to create add-ons—programs that enhance the game’s user interface, add features, and so on. Many of these were very popular—downloaded and used by many other players—and some came to be considered necessary tools for successful raiding. ⇑

4 “Damage Per Second”, i.e. doing damage to the boss, in order to kill it (this being the goal). Along with “tank” and “healer”, “DPS” is one of the three roles that a character might fulfill in a group or raid. A raid needed a certain number of people in each role, and all were critical to success. ⇑

5 “Away From Keyboard”, i.e., not actually at the computer—which means, obviously, that his character is standing motionless, and not contributing to the raid’s efforts in the slightest. ⇑

6 In other words: which of his character’s abilities he was using, in what proportion, etc. Is the mage casting Fireball, or Frostbolt, or Arcane Missile? Is the hunter using Arcane Shot, and if so, how often? By examining the record—recorded and shown by the damage meters—of a character’s ability usage, it was often very easy to determine who was playing optimally, and who was making mistakes. ⇑

Recent Comments